René Laennec, a French physician, was examining a buxom young woman in 1816 when he discovered a less invasive way to listen to her heart than the ear-to-chest method: he rolled up a piece of paper, put it to her heart, and listened through the other side. To his astonishment, Laennec could hear the heartbeat even better than if he’d put his ear to her chest. That simple interaction led to the invention of the stethoscope — the most ubiquitous tool in a doctor’s toolkit, and just one of several medical tools that have evolved from rather primitive versions into their current incarnations.

“Understanding how people solved problems in the past sometimes gives insight into how we can solve the problems today,” says Alan Hawk, museum specialist at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland. “Technology does not stand still. Knowledge does not stand still.”

Here are the stories of how five medical devices came to be:

Stethoscope

Before the inception of this key tool, doctors didn’t use much in the way of instruments. But the invention of the stethoscope was “a big game-changer” — both for respecting the patient’s personal space and for gauging the patient’s health, says James Edmonson, emeritus chief curator at the Dittrick Museum of Medical History at Case Western Reserve University. “It confronted a problem as much cultural and social as it is medical,” Edmonson says. “It was a socially awkward thing to listen to a patient’s heart.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

The same year Laennec made his initial discovery, he invented the monaural stethoscope. It was made from a hollow tube of wood; at one end was a small hole and at the other was a cone-shaped portion. An insert that fit into the cone could be used to listen to the sounds of the heart. With the insert removed, the physician could listen to the sounds of the lungs. With his invention, Laennec made it possible to diagnose bronchitis, pneumonia, and tuberculosis.

In 1851, Irish physician Arthur Leared invented the binaural stethoscope, which allowed a doctor to listen with both ears. In 1852, New York City physician George Philip Cammann perfected it. His version consisted of a bell-shaped chest piece with two long air conduction tubes that provided an increase of sound in both ears. This original Cammann binaural stethoscope was, like many early medical instruments, embellished beyond technical purpose — the ear knobs were made of ivory, and the bell chest piece of ebony.

The stethoscope entirely changed the way doctors diagnosed their patients. “It’s the first time that a tool enhanced the ability to understand what’s happening inside the patient,” says Hawk.

Thermometer

A visit to the doctor’s office will almost always lead to a routine temperature check, but the thermometer as we know it has come a long way in the past several hundred years. German physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit — a skilled glassblower — invented the first thermometer in 1709, which used alcohol contained in a glass bulb connected to a thin tube. The space above the liquid consisted of a mixture of nitrogen and the vapor of the liquid. As the temperature increased, the volume of liquid expanded, moving up the tube which had a scale inscribed on it to assign a number to the temperature. Fahrenheit went on to invent the mercury thermometer in 1714. That instrument operated similarly to the alcohol thermometer, but mercury offered a more precise reading.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

But it wasn’t until 1868 that Carl Reinhold August Wunderlich, a German physician, introduced temperature charts into hospitals with 37 degrees Celsius (98.6 degrees Fahrenheit) as a healthy standard. The thermometer he used was reportedly a foot long and took 20 minutes to register the temperature.

“Doctors always knew that sometimes when people got sick they were hot,” says Hawk. “This allowed doctors and nurses to determine what was hot and what was not.”

The spread of HIV in the 1980s and 1990s ushered in a new fear of infectious disease, and with that came new methods of taking one’s temperature: through the ear, or with a quick swipe of the forehead, Hawk says. Now, doctors generally use digital thermometers that go in the mouth.

The defibrillator

The defibrillator, which can normalize a heartbeat by delivering electric currents to the heart, has evolved from a massive machine on wheels to a small device the size of a desk phone. An article from a 1933 Popular Mechanics discusses an early version of a defibrillator, designed by Albert Hyman and his brother Charles, who was an electrical research engineer. The article describes the machine as a “Self-Starter for Dead Man’s Heart.”

AED.com

AED.com

An electrical engineer, William Kouwenhoven, had been working on a similar device since the 1920s. Kouwenhoven, much like the Hyman brothers, had a fascination with the effects of electrical energy on the human heart. He studied the relationship between the two when he was a student at Johns Hopkins University School of Engineering. Although it was initially tested on a dog, the first use on a human was administered by Claude Beck in 1947, a professor of surgery at Case Western Reserve University.

Beck first used the technique successfully on a 14-year-old boy who was being operated on for a congenital chest defect. “They were trying to do heart massage on him for an extended period. They brought in a defibrillator and revived him,” says George Davis, DO, fellow at the College Physicians of Philadelphia and volunteer at the Mutter Museum, a medical museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Beck administered an alternating current of 60Hz to the boy’s heart and, on the second try, the heart successfully restarted.

The defibrillator used on this patient was made by James Rand, a friend of Beck. It had silver paddles the size of large tablespoons that were used on hearts after the chest had been opened. Rand made two defibrillators that first year of 1947 — one can be found in the Smithsonian, and the other in The Bakken Museum’s collections in Minneapolis, Minnesota, a museum dedicated to medical electricity.

From there, the device only became more powerful, allowing physicians to use it without opening the chest. Nine years later, in 1956, a cardiologist named Paul Zoll used a defibrillation unit to perform the first closed-chest defibrillation.

“In the 1950s they were developed for intensive care units,” Davis says. “The first ones were pretty big, but then you could have smaller ones in little emergency stations in offices.”

The first Automated External Defibrillator (AED) was introduced in 1978, which uses sensors to automatically detect ventricular fibrillation. It wasn’t until 1997 when Florida became the first state to enact a broad public access law requiring the public placement of AEDs. By 2001, all fifty states had enacted defibrillator use laws or adopted regulations.

Modern versions of the device just require the user to press a button and the machine sends an electric current at the right time. “They make it idiot-proof now,” Davis says.

Endoscope

The Greek prefix “endo” means “within,” and this instrument indeed gives doctors a look deep within the human body. The endoscopy procedure uses a long instrument attached to a small camera to examine the interior of a hollow organ or cavity of the body. But what is now a small, flexible tube started out much differently.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

The first endoscope was developed in 1806 by German doctor Philipp Bozzini. Then called a "lichtleiter" or “light conductor,” Bozzini invented it for the purposes of seeing inside bodily cavities. It was constructed of a tube with various attachments, to be inserted into a body canal. A candle and angled mirrors inside the device enabled the physician to see inside the cavity. It was originally thought to be most useful for examining the larynx, but the design later came to be adapted for urological and gynecological applications. Bozzini died in 1810 of typhoid and wasn’t able to develop his invention further.

It wasn’t until 1853 that French physician Antonin Jean Desormeaux presented his device — a modified version of the lichtleiter — to the French Academy of Sciences. The main improvement in his device was the use of a gasogene lamp, which consisted of a burning mixture of alcohol and turpentine and provided better illumination.

The German doctor Adolph Kussmaul made modifications to that instrument and aimed to use it for looking in people’s stomachs. He had the perfect test subject: a sword swallower.

“The very first endoscopes were rigid,” Hawk says. “The patient would basically assume the sword swallowing position.” That device was 47 cm long and 13 mm in diameter and did not bend. They are now flexible and come in sizes as small as 7.5 mm in diameter.

X-ray

One of the first X-rays ever taken was the left hand of Bertha Roentgen — the wife of Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen, a German mechanical engineer and physicist, who discovered the new type of ray in 1895. He quickly found that the rays could pass through heavy paper and even human tissue, but not bones or metal. The discovery made headlines across the world, with researchers recreating Roentgen’s experiments for their own curiosities. Marie Curie, a Polish and naturalized-French physicist, developed the first “radiological car,” nicknamed the “little curie”: a vehicle containing an X-ray machine and photographic darkroom equipment. It could be driven to the battlefield where army surgeons could use the machine to guide their surgeries. “It was an observed phenomenon that when certain energy was emitted by tubes, if there was a photographic plate it could create an image,” says Edmonson. “It caught on like wildfire. It brought together science and medicine in a new way.”

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

But the early versions were crude, and the X-ray tubes were temperamental. Sometimes if the generators — about 8 feet long, 6 feet high, and 4 feet wide — were run for a long time, the tube would go soft, and the physician would have to put it in the oven to give it structure again. William Coolidge invented a more reliable tube in 1913, but people were still oblivious to the deadly nature of the new rays.

“Most early doctors doing it in the early 1900s were dead by the 1930s,” says Hawk. “In the ‘20s people started realizing that those in our profession were dying young of cancer.”

Doctors began limiting exposure by shielding themselves and patients with protective materials. Over time, new ways of peering into the human body began surfacing, like ultrasounds and CAT scans. But X-rays remain the most common and widely available diagnostic imaging technique, given its simplicity and low cost. An X-ray will usually precede a more sophisticated test. And, Hawk says, it was the very first window into the body. “It led to development of other ways of getting the same information,” Hawk says. “It started a revolution.”

A thing of the past

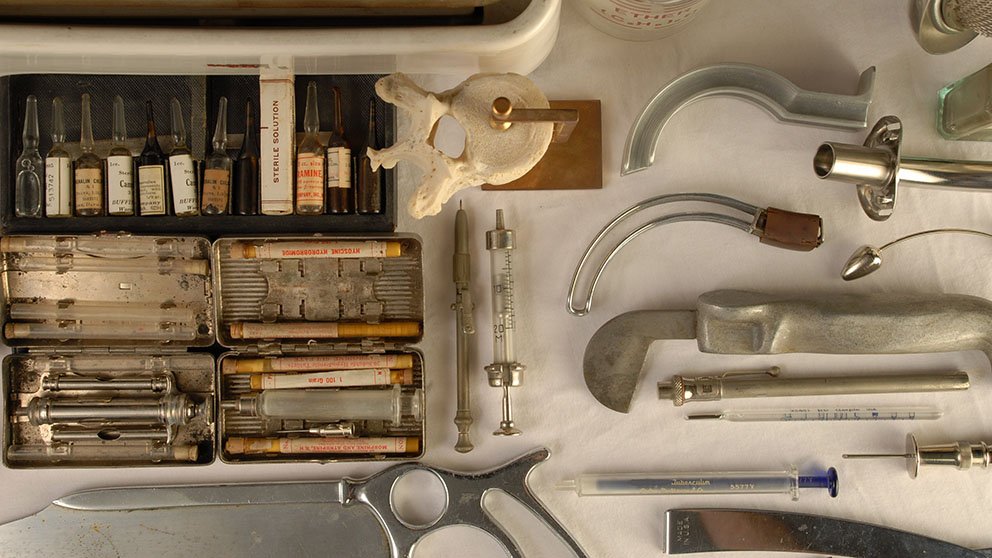

Not all medical devices had staying power. Some are so gruesome they have us thanking our lucky stars they exist only in museums. Here are five tools that, over time, faded from the medical arena.

Artificial leech: This metal cylinder with rotating blades from the 1800s was designed to mimic a leech, by cutting the skin while a tube suctioned out the blood.

The Scarificator: Developed in the early 1700s and used through the 19th century, the scarificator was first used for the practice of bloodletting, and then for smallpox vaccinations. The tool had multiple blades that shot out with the press of a spring-loaded lever.

Amputation saw: One of these from the 1600s was about the size of a large human arm and just as heavy. By the 1800s, they were smaller and lighter — relying only on the surgeon’s speed for a successful operation.

Trepanation Kit: This kit, designed to drill holes in the head, had been used since the Stone Age to treat afflictions from parasites to evil spirits. Thankfully, it has been replaced by the safer and more humane craniotomy equipment.

Écraseur: Used in the 19th century, this tool was made to strangle uterine and ovarian tumors as well as hemorrhoids. It had a wire chain that was placed around the growth and gradually tightened.