As Hurricane Florence blasted toward the East Coast, medical schools and teaching hospitals were again on the front lines of an all-out war against the elements. How lessons learned during 2017's hurricane season helped them prepare for this year's onslaught.

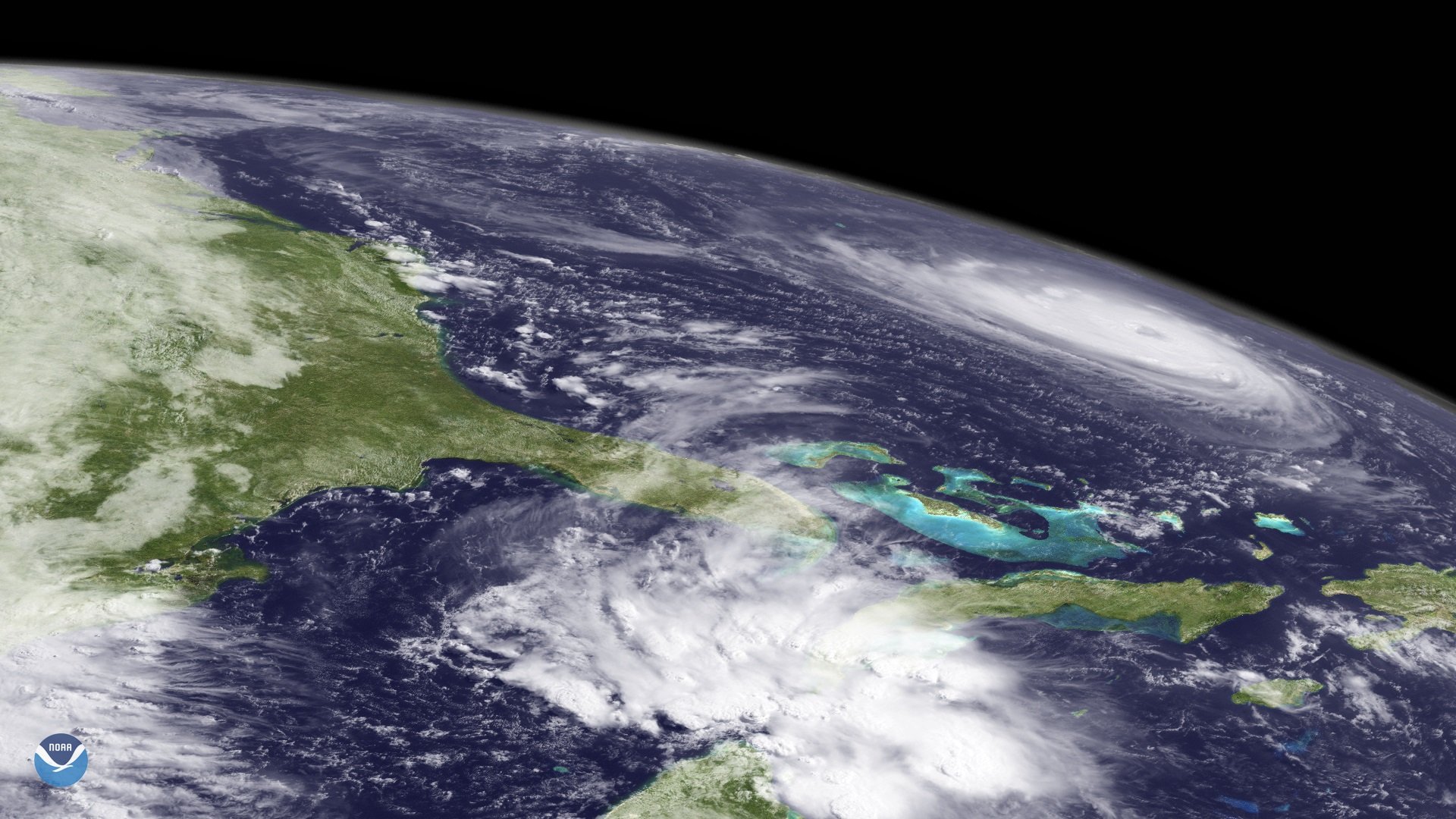

NOAA Environmental Visualization Laboratory

NOAA Environmental Visualization Laboratory

Medical schools and teaching hospitals in North Carolina and South Carolina braced for the worst as Hurricane Florence barreled toward the East Coast. As they prepared, they drew on lessons learned during last year’s devastating storms.

It was a month after Hurricane Maria had torn through the island of Puerto Rico, and Debora H. Silva, MD, associate dean for academic affairs at the University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine, was still scrambling to treat patients in the storm-ravaged coastal municipality of Humacao. Residents had developed sores and skin infections from wading through infested waters. Silva remembers children with disabilities lying bedridden and emaciated, unable to bathe or even get food. The only water they had fell from the sky into their roofless houses.

The conditions in Humacao mirrored those in many of Puerto Rico’s rural areas, where weeks after the storm, residents had little or no access to adequate medical care. Supplies were flowing into the island from the mainland, but a lack of organization and coordination with community leaders meant that those supplies were not getting to the neediest areas.

Maria hit Puerto Rico in September 2017, and a Harvard University study published in the New England Journal of Medicine estimates that as many as 4,645 Puerto Ricans died – 73 times higher than the official estimate of 64. Puerto Rico's true death toll from Hurricane Maria remains elusive as the storm's one-year anniversary approaches. In late August, a George Washington University study estimated the official death toll to be 2,975.

Mere weeks prior to Maria, Hurricane Harvey unleashed catastrophic winds and rainfall on southern Texas, causing $125 billion in damage and more than 100 deaths. Ten days before Maria, Hurricane Irma – one of the most powerful Atlantic Ocean hurricanes – made its way across the Caribbean.

In the wake of these natural disasters, with communications scant, medical professionals on the ground mobilized to care for the sick and wounded.

What they learned has had far-reaching impacts for medical schools and teaching hospitals in all coastal regions and has spurred new initiatives for the 2018 season.

Coordination comes first

“A lot of the casualties of Maria were caused by not being able to get [medical supplies] to people rapidly and not being able to coordinate the delivery,” says Lisa Fortuna, MD, a Boston Medical Center psychiatrist who flew to Puerto Rico to volunteer in Maria’s wake. “When we started to work with municipalities for best distribution sites, that’s when it started working well.”

Community leaders are essential, Silva agrees. “We learned that you need to teach and train and make alliances. Communities may have 200 people or 3,000, but they all need a leader. Sometimes that leader will be chaplain of the church, sometimes it’s just someone who everyone looks up to.”

After Maria, the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus organized interdisciplinary teams to visit municipalities, Silva says. Public health faculty now stay in contact with and train community leaders. “The school has a faculty member who has a master’s in public health, and she is our direct liaison to the communities,” Silva says.

“Suicide prevention systems and hotlines had to go into full gear last season. People are triggered when they hear there’s a tropical storm coming, especially if they’ve been through natural disasters before.”

Lisa Fortuna, MD

Psychiatrist, Boston Medical Center

Private donations are key

“When we have a horrible natural disaster season like we did in 2017 and federal resources are spread thin, that is where the public-private partnership component of response can be very important,” says Christina Catlett, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine at Johns Hopkins University and associate director of the Johns Hopkins Office of Critical Event Preparedness and Response.

When Catlett’s team deploys, it’s with the help of nonprofits like Bloomberg Philanthropies or well-established nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). “When underserved communities have people of means invested in those communities, leveraging those partnerships is the best way to get them on their feet,” she says.

Private donations come with less red tape than government funds and can make a difference more quickly, adds Ileana Nieves, a fourth-year medical student at the University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine. “Private donations and help were the things mostly that kept shelters running,” she says. “When government help came it had to go through a lot of phases to get to the actual community.”

Some of that generosity came from the medical team on the ground, Nieves recalls. One group of doctors and students paid for a teenaged resident with spina bifida — and a complicated urinary tract infection — to fly to the mainland for further care and be reunited with family. “She had lost everything,” Nieves says. “She was really happy and really grateful.”

Need goes beyond physical health

"Suicide prevention systems and hotlines had to go into full gear last season,” Fortuna says. “People are triggered when they hear there’s a tropical storm coming, especially if they’ve been through natural disasters before. There’s a big movement on how to think about resilience-building and helping people get through these anxieties.”

A crisis hotline run by Puerto Rico’s health department received 3,050 calls between November 2017 and January 2018 from people who said they had attempted suicide, according to a report from the Puerto Rico Commission for Suicide Prevention. That number is 246% higher than numbers from the same time the previous year.

Fortuna and her colleagues at Boston Medical Center are working with leaders at mental health training programs in Puerto Rico, including the program at University of Puerto Rico, to establish teaching partnerships with their trainees. “We’ve had some meetings with training directors and are trying to see how we could potentially offer this training to support them.”

Texas saw the same type of increase in mental health needs after Harvey, says Claire M. Bassett, vice president of communications report and community outreach at Baylor College of Medicine. “We provided psychiatrists for two weeks,” she says. “Following that experience, we made provisions in our response plan to have mental health providers available at all shelters.”

People with chronic illnesses are hit the hardest

“Patients with chronic conditions should have a disaster plan in place with their doctor,” says Silva, who could not get her daughter’s insulin pump for a month after Maria. “Everyone with chronic conditions needs to make a preparatory plan with their primary care doctor to make sure they have their medications. I had every privilege you can get in Puerto Rico. If that’s my daughter, imagine other diabetic patients.”

One environmental justice nonprofit in Adjuntas, Puerto Rico – Casa Pueblo – did a needs assessment post-Maria, and has already begun to offer patients with chronic conditions additional resources. “They’ve put solar panels on several houses and created solar panel-powered refrigerators for people who need insulin,” Fortuna says. “They’ve created solar-powered dialysis machines, as well.”

More mobility is needed

Bringing help to those in need – rather than setting up central medical centers – is a priority at Baylor College of Medicine in the wake of Hurricane Harvey, says Sharmila Anandasabapathy, MD, vice president of the college of medicine. “One of the things we want to do moving forward is to create a more nimble response, whereby doctors and facilities can be moved to where they’re most needed.”

To address this, doctors at Baylor are upgrading their portable clinics to have broader capabilities. The expandable clinics – transported like standard 8 x 20 shipping containers – will soon include portable dialysis units to help bring those services directly to patients. “We realized the clinic alone wasn’t adequate,” she says. “You need specialized services.”

“Everyone with chronic conditions needs to make a preparatory plan with their primary care doctor to make sure they have their medications.”

Debora H. Silva, MD

Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, University of Puerto Rico School of Medicine

Medical students need resources, too

“We learned with Irma, because it was a massive hurricane and covered the entire peninsula of Florida and wobbled a couple times,” how important it was to have resources available for medical students, says John P. Fogarty, MD, dean of Florida State University College of Medicine. “The incredible migration of people on the interstate was just amazing. We had a huge traffic jam.”

To simplify the evacuation process, the Florida medical community has created a statewide medical student disaster housing program – an online system that matches medical students who need a place to stay with those students from other schools offering to share their space. “So students told to evacuate can voluntarily go online and find a classmate or tutor in the state” willing to house them for the duration of the storm, Fogarty says. “It’s not just a matter of taking care of patients; it’s taking care of staff and students and everyone else.”

Students learn from the experience

The hurricane aftermath ushered students into various areas of focus, like emergency medicine. For Nieves, the high incidence of conjunctivitis, or pinkeye, she saw among patients from unsanitary conditions informed her decision to become an ophthalmologist. She also wants to return to Puerto Rico after her training is complete.

“A lot of students had in mind plans to go to the mainland after school,” says Nieves. “After Hurricane Maria and seeing how we could help the community, now we have people saying, ‘I want to come back home.’ It gave a lot of students more community patriotism. It’s something that really impacted me.”