If academic medicine is to make headway in reducing the health disparities that affect so many Americans, medical schools and teaching hospitals must invest the time and effort to build trust, develop meaningful relationships, and understand the historical perspectives of the community members they serve. Only then can they develop interventions that are rooted in local wisdom and expertise.

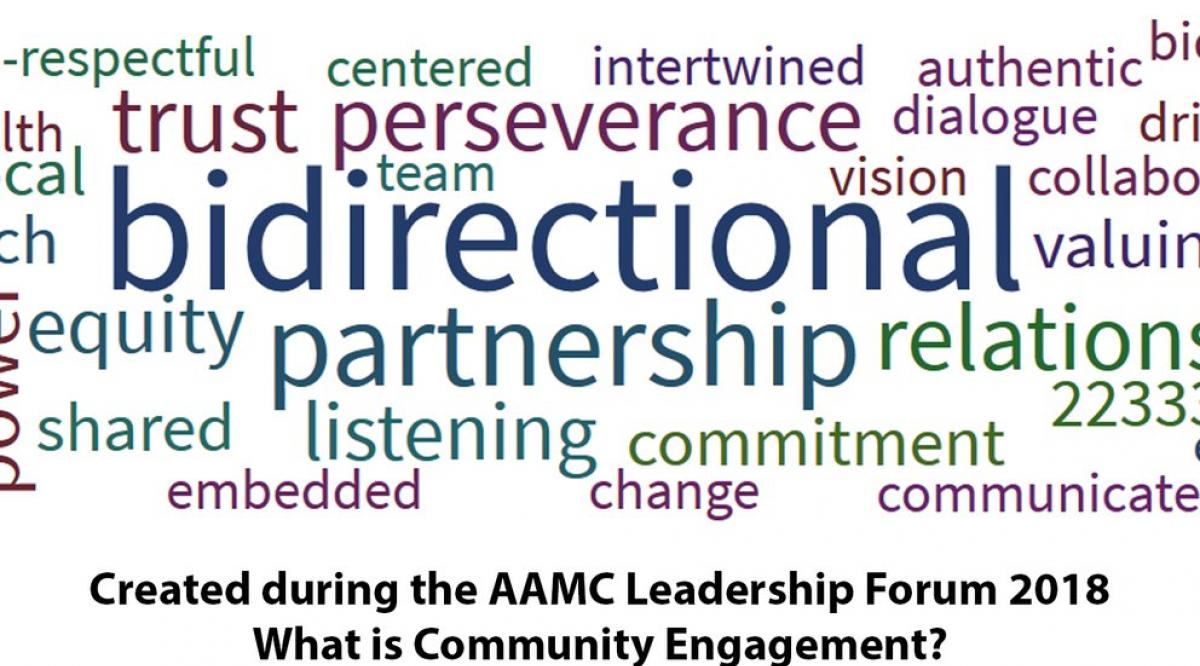

That was the primary message of the 2018 AAMC Leadership Forum, held June 11 and 12, which drew 84 of academic medicine’s top leaders to the AAMC headquarters in Washington, D.C. During two days of spirited discussion, speakers, and participants highlighted the opportunities and challenges faced by institutions who are invested in their communities but not always fully engaged with them.

“Community engagement is not the new word for outreach,” said keynote speaker Consuelo H. Wilkins, MD, MSCI, executive director of the Meharry-Vanderbilt Alliance at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Meharry Medical College. “Outreach is unidirectional. It means you’re offering them your vast knowledge and resources and they should be grateful. Engagement is bidirectional. It requires you to build relationships and trust. You cannot change health outcomes if people don’t trust you.”

“Engagement is bidirectional. It requires you to build relationships and trust. You cannot change health outcomes if people don’t trust you.”

Consuelo H. Wilkins, MD, MSCI

Executive Director

Meharry-Vanderbilt Alliance

Camara P. Jones, MD, MPH, PhD, opened the forum with a thought-provoking talk on traditional ways that academic medicine has addressed health inequities. She used the analogy of patients falling off a cliff when they don’t receive the preventive care they need to maintain good health. How close patients are to the cliff depends on a whole host of issues, from access to healthy food, transportation, and education to differences in the quality of care they receive based on providers’ explicit and implicit biases. Effective community engagement can help providers understand those biases so they can develop solutions that help move patients further away from the cliff. “The barriers to health equity are a narrow focus on the individual, an a-historical perspective, and the myth of meritocracy,” said Jones, senior fellow at the Satcher Health Leadership Institute and Cardiovascular Research Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine. “I would urge us not to be complacent in recognizing and addressing these issues.”

AAMC member institutions have a long history of providing and documenting community benefit, said Malika Fair, MD, MPH, FACEP, AAMC senior director of health equity partnerships and programs. Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, nonprofit hospitals and health systems have been required by law to conduct a community health needs assessment (CHNA) every three years that identifies and prioritizes the needs of the community and requires the development of formal implementation plans to address those needs.

What that has done, said Philip M. Alberti, PhD, AAMC senior director of health equity research and policy, is help institutions recognize the often stark disparities between their most affluent patients and those who live within a few miles of their institutions. It has also reinvigorated many nonprofit hospitals’ commitment to engaging with those communities to address disparities and community health needs in the hope of improving the health of the entire community.

“We often highlight the power of the economic impact of our collective academic medical centers and the fact we are the epicenter of health care,” said Lilly Marks, vice president of health affairs at the University of Colorado and chair-elect of the AAMC Board of Directors. “I challenge us to think about our potential collective power of 151 medical schools and 400 teaching hospitals embracing health status through lenses beyond medicine, such as job creation, local infrastructure, and thriving communities. A community’s health is strongly related to a community’s wealth and well-being.”

Some examples of community engagement highlighted at the forum include:

Understanding historical perspectives. Five years ago, Melissa Lewis, PhD, set out to teach medical students at the University of Minnesota Duluth about the complex challenges and rich culture of Native Americans, whose painful history and distrust of the medical establishment can impede care. At the forum, she shared some disturbing statistics: In a medical setting, native patients are 10 times more likely than non-Hispanic white patients to experience discrimination; a third of surveyed providers have negative stereotypes about Native American people; and 84% of providers say that native-born children are more challenging than non-native kids. Lewis, who is an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation, worked closely with local indigenous leaders to create a curriculum that introduced students to the history of native people, their politics and spirituality, and the medical racism they’ve experienced in the past. Nathan Ratner, a third-year student, says the course deepened his understanding of implicit biases. “The curriculum opened my eyes to specific issues for native patients, but more broadly about how to care for people who are different,” he says.

Financially investing in the community. People who live on Chicago’s West Side have a life expectancy that is 16 years shorter than those a short train ride away, noted Patricia O'Neil of Rush University Medical Center. That disturbing statistic and other inequities drove Rush to fully embrace its status as an anchor institution and, in partnership with community members, to commit to such goals as buying locally, hiring locally, and incubating local businesses. O’Neil, vice president of finance and treasurer at Rush, explained that part of her role is getting leaders to broaden their definition of success. “We’re getting a hybrid return—financial and social,” she said.

Sharing power. When it was first built in 2014, the division of public health at Michigan State University’s College of Human Medicine enlisted community members to fill half the seats on the research faculty search committee. That was a calculated decision on the part of the committee forming the Flint, Mich., campus, which recognized that long-standing distrust of authority culminating with the 2014 water crisis could hamper efforts to engage with the community, according to Wayne McCullough, PhD. “Our relationships are driven by transparency and trust, which is built on mutual history, respect and shared collaboration,” he said. McCullough helps direct the division’s Man Up Man Down Program, which promotes health among black men. To build trust, he noted, institutions “have to be willing to share power, resources, and information.”

Acknowledging a shared history. Darrell G. Kirch, MD, AAMC president and CEO, closed out the forum by reflecting on two personal experiences. Years ago, when he was dean at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, the school renovated an old hospital building—only to discover thousands of bones of slaves beneath the basement floor. The hospital, it turned out, had also owned slaves. Looking back, Kirch said, the institution hadn’t adequately come to terms with its history and the wounds in the community still hadn’t healed.

He contrasted that experience with the 2016 launch of a new medical school at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. The building of the school was planned with input from the community, the admissions committee included local residents, and the initial class drew many of its students from surrounding areas. “I’ve never seen a medical school so interlaced with its community,” Kirch said. “If you pay attention to your history with intentionality, you can do great things.”