The warming planet is already starting to take a toll on human health. In May 2016, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published a position paper in the Annals of Internal Medicine asserting that climate change is a major threat to public health and recommending that physicians and the broader health care community step up to address the issue.

“When the general public visualizes global warming, they may picture a stranded polar bear in a distant, remote area instead of an asthmatic child struggling to breathe in their own neighborhood,” said Howard Koh, MD, MPH, Harvey V. Fineberg Professor of the Practice of Public Health Leadership at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and the Harvard Kennedy School. “The latter image could motivate more people to focus on climate change today and not sometime in the future.”

Given the dire implications for human health, some leaders in the health care community have started to explore strategies to address the new normal of patients suffering from symptoms related to climate change through medical education, patient care strategies, and advocacy.

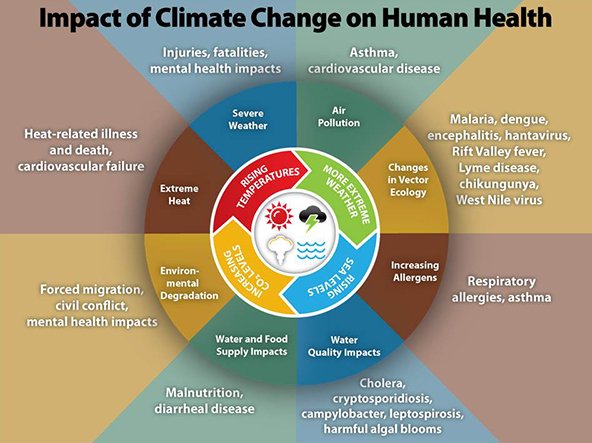

A changing climate will require foresight on the part of the health care community, said Barry S. Levy, MD, MPH, adjunct professor of public health at Tufts University School of Medicine. "We need to develop preparedness and response plans for a wide range of climate-related problems, including heat-related disorders, respiratory and allergic disorders, vector-borne and waterborne diseases, and injuries and displacement due to extreme weather events.”

How pressing is the problem? “This issue basically affects the food we eat, the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the places in which we live. It’s an all-encompassing public health challenge,” said Koh, who is also former assistant secretary for health with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

“Some experts contend that these profound harms rival the fundamental public health challenges posed by the lack of sanitation and clean water in the early 20th century,” wrote Koh in “Communicating the Health Effects of Climate Change,” an article published in The Journal of the American Medical Association, January 2016.

“When the general public visualizes global warming, they may picture a stranded polar bear in a distant, remote area instead of an asthmatic child struggling to breathe in their own neighborhood.”

Howard Koh, MD, MPH

Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health and the Harvard Kennedy School

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) and George Mason University (GMU) Center for Climate Change Communication published results of a survey in December 2015 that showed “a large majority of AAAAI members” reported patients experiencing health effects from climate change, primarily allergic or respiratory disorders due to longer pollen and ozone seasons, injuries due to severe weather, or increased severity of chronic disease symptoms.

Physicians view climate change as a “threat multiplier” or “risk multiplier.” “It makes bad things worse,” said Jay Lemery, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine and section chief of wilderness and environmental medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. The most vulnerable patients will be hit the hardest, including the elderly, the young, the poor, and people with heart, lung, and kidney issues, said Lemery, who also co-edited Global Climate Change and Human Health: From Science to Practice.

A pervasive problem

“I think the most important point is that climate change touches on so many different aspects of public health,” observed John M. Balbus, MD, MPH, senior advisor for public health at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. He cited “Heat stress for people with chronic diseases; more intense flooding and extreme events causing physical injuries, psychological stress, and damage to critical infrastructure and residences; changes in the range and transmission of a host of infectious diseases; and mental health impacts,” as among the health concerns influenced by changes in the Earth’s climate.

According to Levy, injuries from severe weather events are one of the most obvious signs of global warming. “Not every severe weather event is due to climate change,” but warmer water in the North Atlantic probably contributed to the severity of Superstorm Sandy, said Levy, who is also co-editor of the 2015 book Climate Change and Public Health.

Levy noted, too, that warmer and longer heat waves are leading to more cases of heat-related deaths and heat-related complications in cardiovascular, pulmonary, and other disorders. A three-week European heat wave in 2003 killed 40,000 people, including 15,000 in France alone, he said. “Some of that is thought to be due to climate change.”

In addition, more cases of food-borne and water-borne diseases brought on by flooding have occurred not only in countries such as Pakistan, but also in U.S. cities such as Milwaukee, where heavy rains overloaded the sewer and storm water systems in 2010.

Too much or too little water can disrupt food supplies, too, Balbus noted. “In places like Alaska you can have a loss of livelihood, loss of food supplies or migration of those food supplies, and increasing risks of infectious diseases all in the same community,” he continued. “That’s an instance where climate change is exacerbating a combination of mental-health and physical stressors all in one population.”

Other risks of global warming cited in the ACP position paper were an increase in mosquitoes, ticks, and other “climate-sensitive vectors”— including those for dengue fever, chikungunya, and Zika virus —that could spread to newly hospitable environments. Author Ryan A. Crowley, writing on behalf of ACP’s Health and Public Policy Committee, noted that drought related to climate change could be a factor in increasing the spread of West Nile virus because birds and other vectors compete for water with people. Water scarcity can also lead to poor sanitation and cholera outbreaks.

Physicians and medical educators step up

Mona Sarfaty, MD, MPH, director of the Program on Climate Change at GMU’s Center for Climate Change Communication and lead author of the AAAAI survey, said GMU’s Center is encouraging physicians to take a lead in environmental sustainability and advocacy in addressing health-related climate change issues.

Only about 40 percent of 1,204 Americans surveyed believe that people in the United States are being harmed by climate change now, according to a poll (March 2016) conducted by GMU and the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

“The current debate around climate change tends to be that it’s an economic, environmental, and political issue, but it is also an individual health and a public health issue.”

Wayne J. Riley, MD, MPH

American College of Physicians

Koh said doctors can make a difference just by talking about climate issues with their patients. “If [clinicians] can weave the climate-change theme into discussions or even just mention the term when they’re caring for patients who have related health impacts, that alone could be a service,” he said.

Balbus has begun to see medical school faculty members educating themselves about the health implications of climate change and offering courses or grand rounds on the topic. “I believe that students will increasingly demand information about sustainability of health practices and the health impacts of climate change,” he said.

The McGovern Medical School of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston is among the schools starting to add content on climate change to the curriculum. In the spring of 2016, the school offered “Climate Change and Human Health,” an elective course for medical students at its Center for Humanities and Ethics. The course covered information about global warming, activism, and the ethical issues surrounding climate change, among other topics.

Tulane University School of Medicine hosted “Green Week” and awarded prizes to students who reduced waste, rode their bikes to school, or took other environmentally-conscious actions.

Other health care professionals have become advocates. In 2015, a number of concerned public-health leaders, health care organizations, medical schools, and medical associations issued “A Declaration on Climate Change and Health” that called for actions to protect public health. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Lung Association, and the American Thoracic Society were among those signing the declaration, in addition to a dozen AAMC-member medical schools.

Taking responsibility for the future

To prepare the next generation of health care professionals, the White House hosted a workshop in 2015 of deans from medical, nursing, and public health schools “to share practices and align common objectives to advance knowledge on the health impacts of climate change.”

“The current debate around climate change tends to be that it’s an economic, environmental, and political issue,” said Wayne J. Riley, MD, MPH, immediate past president of ACP. “It is also an individual health and a public health issue.”

In its position paper, the ACP called on physicians and the broader health care community to be proactive in tackling climate change health issues. The paper recommended that hospitals engage in environmentally sustainable practices that reduce carbon emissions and educate the public, lawmakers, and colleagues about the health risks posed by climate change.

“The health care sector consumes a massive amount of energy, ranking second-highest in energy use after the food industry and spending about $9 billion annually on energy costs,” said Riley. Instead, he added, “We need to set the example.” ACP created a toolkit to help physicians, their colleagues, and their staffs adopt environmentally sustainable practices in their work setting.

Koh noted that members of hospital committees can advocate for green practices and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification. The HHS Sustainable and Climate Resilient Health Care Facilities Initiatives also produced a toolkit that includes guidelines on land use, building design, and ways to reduce energy consumption and waste for hospitals, nursing homes, and other large facilities.

“The health of the public is at stake,” Levy stressed. "Physicians and other health professionals need to help make adaptation to climate change and mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions high priorities.”