The asthma patient was back for her third ER visit, and it wasn’t clear why. Soon, care team member Cheryl Garfield solved the mystery: The woman’s lungs were irritated from living in the damp, poorly ventilated basement of a homeless shelter. In short order, Garfield marched down to the shelter and arranged for a healthier room. And a few months later, she helped the woman move out entirely.

Garfield is a member of a unique and sometimes-overlooked cadre of personnel: community health workers (CHWs). Also known as patient navigators, lay health advisors, and other titles, CHWs are front-line public health workers trained to address a host of obstacles to healthy lives.

What’s more, they possess something that doctors don’t always have: a deep understanding of local issues and resources. CHWs often speak a patient’s language, both literally and metaphorically. And they’ve increasingly become a key part of some patients’ health care team.

CHWs might exercise with patients, monitor their blood pressure, go with them to doctor’s appointments, or visit when they’re lonely. Throughout, they help address a vast array of social determinants of health, from food insecurity to lack of health insurance.

“Four years ago, people were saying, ‘What’s a community health worker?’ Now they’re saying ... ‘Can you help me figure out how to use them?’ ”

Jill Feldstein

Chief Operating Officer

Penn Center for Community Health Workers

“Social determinants have a much greater impact on health than the health services system,” says Arthur Kaufman, MD, vice chancellor for community health sciences at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UNMHSC). “All those social determinants can be improved simply by having someone who is knowledgeable about them and can act on them.”

And thanks in part to research on their contributions, the number of CHWs is on the rise, with a predicted 16% growth from 2016 to 2026. It’s hard to pinpoint the total current count of CHWs: estimates range from 25,000, according to national CHW organizer Sergio Matos, to 118,500 in federal data that include health educators.

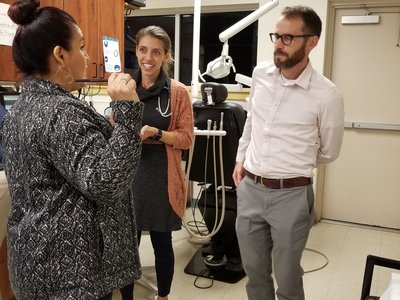

Meanwhile, as medical schools and teaching hospitals seek to boost access, provide quality care, and lower costs, they are increasingly drawn to CHWs. In fact, growing numbers of academic medicine institutions are hiring CHWs, creating programs to train them, welcoming them into multidisciplinary team meetings — and exploring how best to learn from them.

When CHWs lead

Back in 2014, leaders at UNMHSC were shocked by the research findings: Nearly half of 3,000 screened patients lacked a job, housing, or some other crucial socioeconomic need.

Soon, they established a project to identify needs among all clinic patients and to connect them with CHW support. Among the results was an estimated return on investment of $4 for every dollar spent. Since then, the effort has expanded to multiple UNM sites.

“We are unique in that we are trying to integrate community health workers into virtually every place we see patients,” says Kaufman.

At first, some staff resisted the changes. For example, they asked how CHWs differ from social workers. “Social workers are quite highly trained, and there aren’t enough of them, and they’re more expensive,” Kaufman explains. “In time, CHWs clearly demonstrated that they could free [social workers] up to focus on more complex issues.”

“[W]e are trying to integrate community health workers into virtually every place we see patients.”

Arthur Kaufman, MD

University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center

Lidia Regino is one CHW who works with UNM. For a while she directed One Hope Centro de Vida Health Center, a community clinic that uses UNM residents and is run entirely by CHWs. Regino describes CHWs as human bridges.

She recalls one medical resident who assumed she’d find it easy to communicate with patients because she was from an immigrant family. “She didn’t take into account that in Hispanic culture, people can put the doctor on a pedestal, so they sometimes withhold information,” Regino says. “But as a CHW, I could get the necessary information and help connect the patient to the doctor.”

And she can talk to the physicians. At the end of every One Hope visit, patients pass through a “Salida,” an exit interview designed to check whether they’ve understood — and can use — their care plan. “Then CHWs go back and talk to the providers and educate them,” Regino explains. “We can say, ‘Whatever you prescribed is not going to work because the patient can’t pay for it. You need to find something else.’”

What’s more, Regino notes, the physicians will listen. “In a typical clinic, the doctor has the last word, but here we are on equal terms,” she says. “Here we have that power.”

A significant "IMPaCT"

Over the past eight years, CHWs from the Penn Center have reached thousands of high-poverty Philadelphia patients. Using the center’s Individualized Management for Patient-Centered Targets (IMPaCT) model, they have chipped away at stubborn problems such as obesity and smoking — and reduced hospitalizations by 65% among patients with chronic conditions.

The center, which is funded by Penn Medicine, provides varied resources for replicating IMPaCT and so far has disseminated information to hundreds of institutions nationwide.

Given their success, a few years ago leaders from the center and the Perelman School of Medicine had a lightbulb moment: Why not use CHWs to teach medical students? So in 2013, they launched the country’s first CHW-led elective, an apprenticeship that has sent more than 60 students into local communities.

“Because being a preceptor is an authoritative role, the CHWs don’t feel shy about saying certain things,” notes the center’s Executive Director Shreya Kangovi, MD. “They think, ‘It’s my responsibility that by the end of the month you know what it’s really like to grow up in this community.’”

What that’s like, Kangovi says, can mean not having enough food, trouble finding a free health clinic, and a daily drip of near-constant stress.

But students not only witness such obstacles; they also get the emotional lift of helping address them. Students have, for example, connected patients to a food bank, navigated them through complex paperwork, and even found one a soothing pottery course.

“We can learn all the pathophysiology we want, but if patients can’t access healthy behaviors because of barriers in their community, we can’t really help them.’ ”

Joanna Stephens, MD

Penn Medicine

Joanna Stephens, MD, a recent grad, hopes more schools will launch similar training programs. “When I see a patient now in the hospital, I fully understand how CHWs can help them,” she says. “We can learn all the pathophysiology we want, but if patients can't access healthy behaviors because of barriers in their community, we can't really help them.”

A bright future

Integrating CHWs into health care systems is not without its obstacles. For one, some medical staff may be perplexed by a career with no nationally recognized standards for training or certification. Others may fear that collaborating will steal precious time from already overloaded schedules. What’s more, funding issues — grants that dry up, for example — also can hobble CHW efforts.

Sergio Matos, who is working to create the first national CHW association, is exploring ways to address these issues. For one, he notes, teaching medical staff how to collaborate with CHWs can make a big difference, as can team-based care models. In addition, establishing CHW certification guidelines may help, he says, if they don’t constrain the flexibility at the heart of CHW care. And new government reimbursement approaches, including bundled payments, may enable more CHW funding.

Meanwhile, the future of CHWs looks promising, particularly if a Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM) program in Atlanta, Georgia, is any indication.

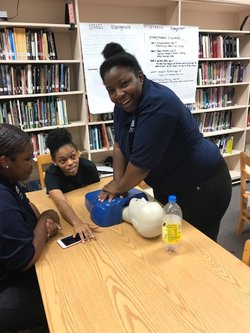

Three years ago, MSM created the country’s first CHW program for high schoolers in an effort to address a triad of issues: health, education, and unemployment. During the year-long training, participants learn skills ranging from CPR to health coaching and monitor several patients’ progress. In addition, they design and implement community-based projects that have included a heart-healthy “CholeStroll” walking project.

The training has been so successful that Georgia officials are thinking about trying it in rural regions, and MSM is developing an online curriculum for institutions interested in replicating it.

Prayer Idowu, 17, found the hands-on training eye-opening. “I saw that not every staff member directly heals patients,” she says. “The CHW can be that person a patient can talk to about personal things, a shoulder to lean on, someone who helps you get what you need.”

Idowu, who thinks she’d like to be a doctor one day, says the program has been inspiring. “I want to pursue helping everyone that needs help,” she says. “There’s a great joy that helping a person brings you.”