As an undergraduate student at Seattle Pacific University, Denise Martinez, MD, had dreamed of becoming a physician. But she kept her ambition a secret, doubting her ability to thrive in medical school.

By chance, she came across a flyer for what is now known as the Summer Health Professions Education Program (SHPEP), which has introduced nearly 30,000 first- and second-year college students to careers in medicine, dentistry, and other health professions over the past 30 years. Her decision to participate would be pivotal.

Martinez gained the confidence to apply to medical school and became a family medicine physician. Her experience even led her to develop and lead the SHPEP site at the University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine. It was a longtime goal fulfilled for Martinez, now associate dean for cultural affairs and diversity initiatives at Carver College of Medicine. She loves telling SHPEP students that they too can succeed in health-oriented careers — the same message she once received.

“This program literally changed my life,” says Martinez.

Many students like Martinez have been deeply affected by SHPEP since it began in 1989. The program, led by the AAMC and the American Dental Education Association (ADEA), offers college students who identify as economically disadvantaged or from a group underrepresented in the health professions a six-week crash course in how best to prepare for a health care career.

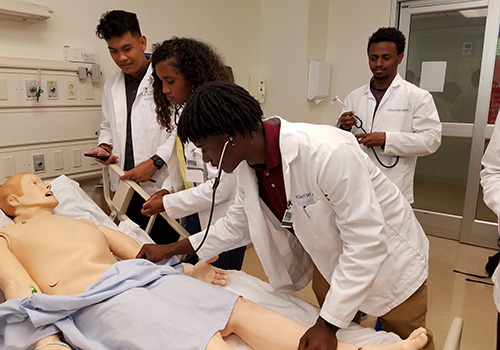

Students receive academic enrichment in the basic sciences, hands-on learning, and mentorship from professionals in the field, all at no cost thanks to funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF).

Students’ success following the program has been well-documented. According to internal AAMC data, about 66% of SHPEP participants on average apply to medical school, with nearly the same rate accepted. And a study from Mathematica Policy Research found that participants were slightly more likely to apply to medical and dental school as well as matriculate than nonparticipants.

“Having that community, that cohort of like-minded folks who have a similar passion, a similar dream, the multiplication effect of that on how you move forward as a student of color, as a student from an underrepresented background, or from a disadvantaged background, is immense,” says Victoria Gardner, EdD, MEd, assistant dean for equity, diversity, and inclusion at the University of Washington School of Public Health. “And to know that you're not alone, and to be given the tools to add to your own tool kit, it's powerful.”

Many versions, one mission

Even though its core mission has remained the same, SHPEP has undergone plenty of iterations in its three decades. It began as the Minority Medical Education Program (MMEP), serving students from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds interested in pursuing medicine. Over the years, the program has continuously expanded to encompass more career pathways and more students from underrepresented groups, with the latest version established in 2016.

“The program has changed to remain responsive to the ongoing needs of not only what's happening in terms of diversity in higher education, and the health professions, but to also be responsive to the public health needs,” says Norma Poll-Hunter, PhD, deputy director of SHPEP and senior director of human capital initiatives at the AAMC. “It really has taken into account how we’ve become more diverse as a nation, but also to address the fact that we need to work in an interprofessional modality in order to advance health care.”

At every program site, students participate in basic science courses and small group rotations in health care settings, strengthen their study and learning skills, and learn about health policy. Students also are taught financial literacy and planning as well as career development.

Each of the 12 program sites functions slightly differently depending on its educational offerings, which may include pathways in public health, physical therapy, dentistry, nursing, medicine, pharmacy, optometry, and physician assistance.

“We think it’s really important for…health professionals to have that broader understanding of health and to see where they fit and what their role is in contributing to people in the community,” says Kay Felix, MD, managing director for the Leadership for Better Health portfolio of programs, including SHPEP, at RWJF.

No matter what career pathway students choose to explore over the summer, they have the support of their peers, professors, and staff who are excited to see them thrive, especially in settings where they have not historically been highly represented.

SHPEP is an opportunity to give back for Hilda Hutcherson, MD, senior associate dean in the Office of Diversity and Multicultural Affairs at Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, a SHPEP site. She was a first-generation student from a rural, low-income community who depended on a strong support network on her path to becoming a physician.

“I could not have achieved what I achieved without many people who acted as my supporters, my mentors, and my guidance counselors,” says Hutcherson. “It’s really important to me to look out for the same kind of kids from the same kind of backgrounds who may never have been told that they could achieve something like being a doctor.”

Creating a more diverse health care workforce is especially important considering a projected shortage of physicians nationwide. By 2032, the United States will experience a shortage of up to 122,000 physicians, according to the AAMC. Disadvantaged communities will face the greatest burden in lack of access to quality health care. But future health professionals who themselves are from these communities can change outcomes for the better, experts say. SHPEP has already produced more than 7,000 physicians and nearly 600 dentists to work toward that goal.

“To anticipate a future where the face of the health professions looks like the face of America ... means that we've got to aggressively continue to pursue opportunities for people who come from underrepresented minority backgrounds in particular,” says Richard Valachovic, DMD, MPH, former ADEA president and CEO. “The more people that we’re able to get out there who look like parts of the population that have not had access to care in the ways that the majority population have is a wonderful thing.”

Here's to thirty years

SHPEP will be honoring its thirty-year anniversary at a national alumni conference taking place Aug. 17 at the AAMC. Former SHPEP participants will come together for a series of professional development workshops and networking with alumni from all iterations of the program. Representatives from RWJF and other organizations will also be speaking at the event.

The conference will also be an opportunity to celebrate alumni who have made strides across health professions. Felix is proud to see SHPEP alumni continue to give back to the program, supporting current scholars and even becoming site directors.

“People that show up in this program stay. They care,” says Felix. “A lot of them come from communities where there are not a lot of opportunities. They have personal experiences of wanting health and health care to be different, so they come in really caring about their communities, caring about the field, wanting to make a contribution.”

David A. Acosta, MD, the AAMC’s chief diversity and inclusion officer, has a special connection to the program. He was the principal investigator for the Summer Medical Education Program (SMEP) and the inaugural Summer Medical and Dental Education Program (SMDEP) at the University of Washington School of Medicine. He is excited to see where alumni ended up.

“It always brings me heartfelt joy to hear about their successes,” says Acosta. “Some have realized their dream and are in medical, dental, or another health professions school, some are even faculty at our health professions schools, while still others are trailblazers in other fields making a difference in policy, education, public health, and research. This has validated for me that pipeline programs do matter and do make a difference.”